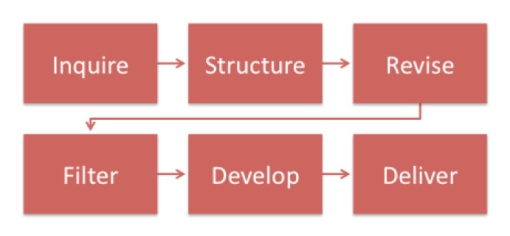

Planning a proposal to win a grant from a unit of state or local government is a 12-step process. Its final six steps are: Inquire, Structure, Revise, Filter, Develop, and Deliver.

INQUIRE: Contact the program officer (or other contact person) for the selected grant opportunity. Be prepared to pose intelligent questions, not ones you should be able to answer on your own. Verify your organization’s eligibility if you have any doubts. Learn about upcoming key dates in the funding cycle. Ask for a copy of the Request for Proposals (RFP) if it is not available online. Ask for names of contact persons and other public information about recent grantees. Ask how to make requests under your state’s version of the Federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) if you plan to submit formal requests for copies of proposals recently funded under the same grant program.

STRUCTURE: Prepare three checklists based on each selected RFP. Create a checklist for the proposal’s content requirements, particularly its selection criteria. Make a second checklist for your key selling points as they relate to the RFP’s selection criteria. Finally, create a checklist for the RFP’s format and submission requirements. Note that while many state and local agencies now require online applications, the requirement is not yet universal.

REVISE: Refine your project after your inquiries with the program officer, review of each RFP, and creation of your three checklists. Adjust your project plans to reflect the insights gained. Do not distort a project to fit priorities declared in an RFP. Continue to revise and refine your project’s key selling points. Compile a list of new questions as they arise.

FILTER: Contact the program officer or a similar state or local agency program management representative. Submit to that person a synopsis or draft of your revised proposal and ask for project-specific feedback, if allowed. Incorporate the input in a further revision to the proposal. Thank the program officer or other representative for the non-binding administrative guidance provided to you.

DEVELOP: Fully develop the plans for the project. Establish organizational capacity. Substantiate needs. Formulate goals and objectives and specify key activities. Develop timelines. Identify appropriate staff. Articulate evaluation plans. Delineate itemized budgets. Comply with each specific grant program’s selection criteria, funding priorities, performance indicators, and instructions.

DELIVER: Write and submit a timely full proposal that is scrupulously consistent with the grant program’s selection criteria, funding priorities, performance indicators, and instructions. Throughout the state or local agency’s proposal review process, remain patient while waiting for notification of results. Respect with equanimity the ultimate funding decisions—fully funded, partially funded, or not funded—of the state or local agency grant maker.